The Art of Affinage

The world’s most distinctive cheeses—many handcrafted in Wisconsin—share a common trait: a strong finish. Affinage, the final step in the cheesemaking process, is the art of aging cheeses. It refers to refining cheeses to optimal flavors and textures through aging. An affineur manages the environment while sculpting the cheeses with every decision and every technique used (and not used) to coax their ideal characteristics and personality, as no two wheels or blocks are the same.

What Happens When Cheeses are Aged?

The protein structure and fats gradually break down as cheeses age, contributing to softening and flavor development. The cheeses are aged in “cheese caves” or climate-controlled, cave-like ripening rooms, where they are monitored and maintained to maturity. A myriad of finishes may be applied here—salting, ashing, washing, brushing, rubbing, soaking and piercing.

Finishes with Flair

Like fine art pieces, cheeses are babied and guided to their peak ripeness during aging. These techniques help express the flavor complexity of the milk while the cheeses age, form rinds, manage microbes and molds, and ward off potential defects. Some finishes are used for nearly all aged cheeses, while others are used when crafting specific families.

Salting

Often the first step in affinage, most cheeses are treated with salt before hooping or when unmolded from their forms. Salt regulates the growth of microbes on the surface and in the body of the cheese during aging.

Ashing

Some cheeses, like soft-ripened brie, are sprinkled with finely powdered vegetable ash after salting. The alkaline ash dries and deacidifies the cheese’s surface, promoting rind formation and a softer curd.

Washing

Smear-ripened cheeses are periodically washed with salt brine to cultivate bacteria and yeasts that produce their well-known pungent aromas and meaty flavors that cheese lovers crave.

Brushing

Natural rind cheeses may be brushed to control mold growth. This step ensures that rinds develop slowly and evenly while protecting the cheese’s interior.

Rubbing and Soaking

Rubbed with olive oil and herbs or seasonings like black pepper or spices or soaked in wine or spirits, natural rind cheeses benefit from the vibrant colors, aromas and flavors.

Flipping and Turning

Cheeses must be flipped or turned during aging to ripen evenly—weekly, daily, sometimes twice a day—otherwise, gravity pulls moisture away from the body of the cheese.

Piercing

Blues are created by plunging a needle into the cheese dozens of times per side. The openings invite oxygen into the cheese, allowing veins of blue mold to emerge and spread throughout the paste.

Time

Although not a physical process, time is one of the affineur’s most important tools. Desired characteristics in cheeses evolve with time, which ranges from two weeks to several decades.

Rind Time

Cheeses ripen internally in the body of the cheese or externally on the surface. The rinds are carefully cultivated layers of microflora. They form through a process known as microbial succession. While rind ecosystems are quite complex, they create the signature characteristics of the cheeses that connoisseurs love.

There are several types of rinds. The bloomy rinds on cheeses like brie and camembert style contribute to their luxurious textures and mushroomy flavors. Washed rind cheeses like limburger and aged brick are handcrafted by smearing brine on their surfaces, creating conditions for funky aromas and pungent flavors to develop. Flavored rinds are crafted by soaking or hand-rubbing cheeses with ingredients like beer, balsamic vinegar, rosemary and olive oil, and cinnamon and paprika. Young natural rind cheeses are treated with salt brine, which helps produce naturally occurring molds. Cheeses with bandage-wrapped rinds are wrapped in cheesecloth, like those on some artisan cheddars, allowing them to breathe during aging, yielding a drier, more crumbly texture and varying flavors. Lastly, waxed rinds seal in moisture, helping protect pressed cheeses, like gouda, while encouraging their distinct flavors.

Should you eat the rind? We don’t rind if you do! Mostly, cheese rinds are edible, except for cloth, wax and bark. While there’s a lot to learn about cheeses by eating the rinds, not every rind is intended to be eaten—and since palates are so subjective, it’s a personal preference. The rind of a cave-aged cheddar will be chewy and musty, likely to detract from the cheese’s flavors. However, a delicate rind on brie offers an earthy but delicious counterpoint to the cheese.

Explore the World of Cheese

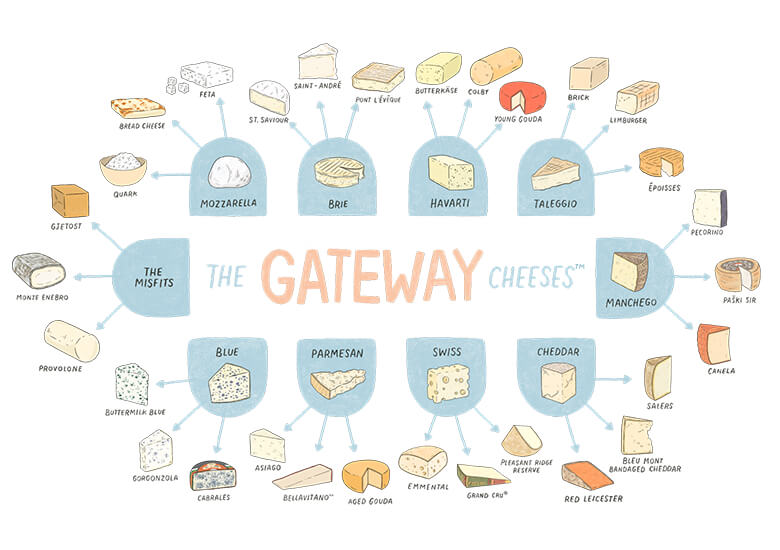

Discover new favorites with Gateway Cheeses™, founded by cheese expert Liz Thorpe. The starter cheeses are familiar to most cheese lovers. Each offers three cheese offshoots grouped by common sensory traits—creamy and mild, buttery and nutty flavored, etc. For example, you love mild, buttery and slightly sweet havarti. Then you may also enjoy colby with its mild flavor and moist, creamy texture; buttery melt-in-your-mouth butterkäse; and slightly sweet young gouda. They’re all aged for a short time and pair easily with other foods, much like havarti.

The Big Cheese: Liz Thorpe

Author of “The Book of Cheese,” the founder of The People’s Cheese™ and Gateway Cheese™, and a guest speaker at the Art of Cheese Festival, Liz Thorpe shares about the art of affinage and how curious cheese lovers can find their new favorites.

Photo credit: Ellen Silverman

Can you recommend a Gateway Cheese™ for someone wanting to explore aged cheeses?

Swiss and parmesan are my two favorite Gateway Cheeses™ to explore the flavor and complexity that longer aging can bring. From Wisconsin, I can’t get enough of Uplands’ Pleasant Ridge Reserve and Marieke® Gouda Reserve.

How do flavors or textures change as cheeses age?

Cheeses aged longer will be increasingly firm to hard in texture. Time means moisture loss and concentrated flavors. Also,

cheesemakers add enzymes that don’t activate until specific salt, water and acidic conditions are reached. These enzymes essentially “turn on” around four, six or nine months into the aging process, changing the structure of fats and proteins and releasing chemical compounds that you experience when you taste the cheese. That’s why milk may be neutral in flavor, but cheese is not.

Share one of your favorite finishing techniques applied by a Wisconsin cheesemaker.

Widmer’s Aged Brick is a semisoft cheese washed in brine. When I visited the plant, I learned that the wash is more like a mother culture—it’s a brine that has been used for years and topped off over time with new salt water, but it contains the microflora from generations of that cheese.